By Tarek Michael Chouja, Director of FTI

“ANY FOOL CAN GO TRAIN MORE. IT TAKES COURAGE TO REST”

Goran Kenntta – Swedish Sports Psychologist

How many of us (coaches or fitness/sporting enthusiasts value recovery? How many of us even think it is a waste of time?

Well my intention with this blog is to not convince you but lead you to the water where you choose to drink the good news of recovery or not.

As you read, watch and consume the content, do so with an open mind and yes a sceptical one also. Healthy scepticism balanced with an open mind is the best way to decipher and interpret the information of any kind.

The WHY of Recovery

Including recovery techniques into your daily life is not simply cooling down after a hard session. It is recalibrating the body (which includes the heart, brain and gut) physically and psychologically after a training session; after a hard day’s work; after a holiday (believe it or not) and simply incorporating it into you daily routines.

Some recovery strategies are more conducive to post training sessions; however the purpose of Recovery training is to reset the body and the mind and synergise the two. We could say it is a return to readiness. A readiness to be regenerated mentally at work and physically for the next training session.

The WAY of Recovery

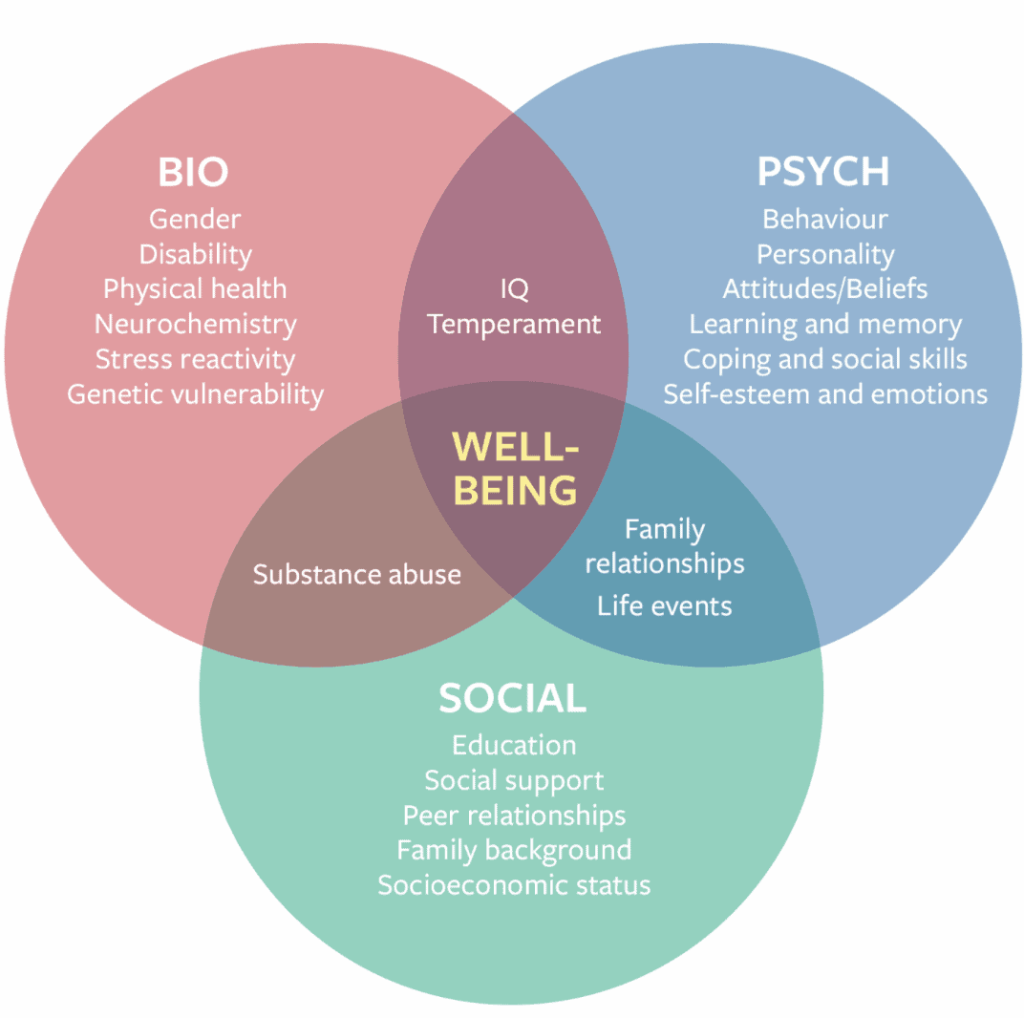

Recovery training falls under the Bio-Psycho model. Within this system we have modified and somewhat simplified the concepts to fall under the following categories:

Bio (aka physical factors)

In layman’s terms, this is the skeletal and soft tissue recovery components that act to restore and optimise soft tissue and skeletal adaptations and rebalance the bio-chemistry within the body to maintain a neutral PH balance. Exercise elicits the stress hormone cortisol which gets us through a tough training session. It serves a purpose within the session and during states of emergency. But we need to learn to down-regulate this hormone post training and indeed in our daily lives

Performing a series of Neurodynamic Mobilization techniques empowers us and the client to take responsibility and learn how to do it ourselves. This is known as a self-directed approach to recovery.

In the recovery checklist, we have included certain methods that are commonly used yet not restricted to:

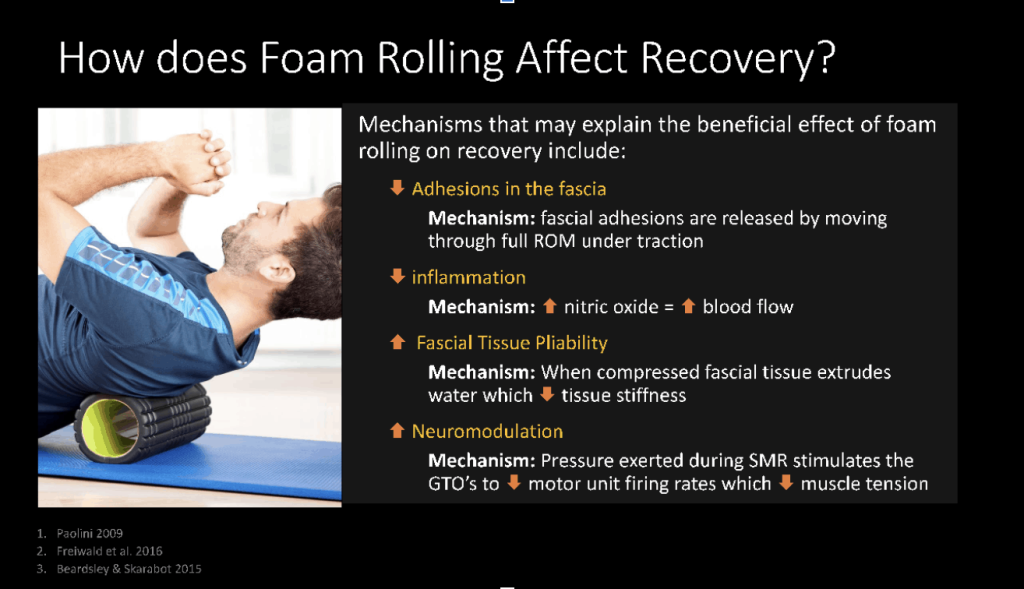

Foam rolling/trigger point therapy

This is soft tissue manipulation designed to realign the myofascial matrix and reduce muscular tension and adhesions. Foam rolling triggers a hormonal and neural response such as “increasing parasympathetic activity whilst reducing cortisol concentrations” which may explain the observed reduction in muscle soreness following vigorous exercise training.

Watch for a quick overview of

Foam rolling Drills

-

- Lower limb

-

- Upper Limb

Trigger point Drills

-

- Trigger ball for foot

-

- Walk the rope

Stretching techniques/flows

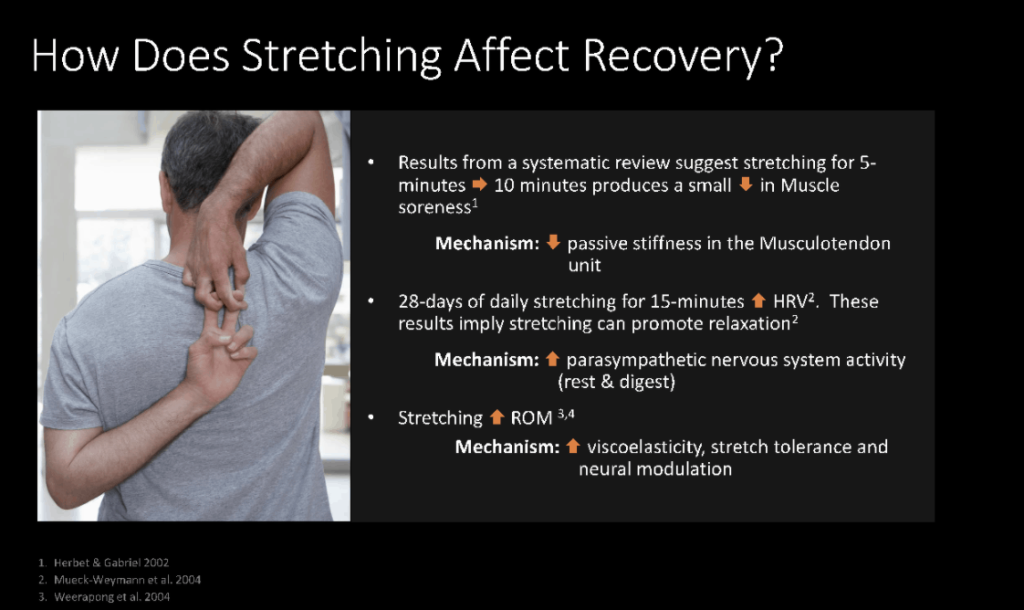

the effectiveness of Static stretching for flexibility has been vigorously contested in the scientific community of late; however, our understanding of static stretching in the recovery process is still in its infancy.

A recent article titled The Case for Retiring Flexibility as a Major Component of Physical Fitness https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31845202/ , questions the resourcefulness i.e. amount of time spent on this modality, and thus necessity of including static stretching within a given training program. You may investigate this for yourself as it is not the aim of this article to rubbish static stretching.

There are however some positive implications of stretching as a form of recovery as indicated in the image below

The contention raised with stretching flows poses a different way of looking at and including stretching as a form of recovery. The method of a flow is thus:

- Pick a base position such as prone (front of body)

- Work 3-4 key transitions. Each transitionary phase will be held for 3-5 seconds before flowing into the next one.

- Repeat for a desired amount of times

See the below video for an example of a prone static flow with a rotational elemen

Stretching flows provide a greater neural stimulus and offers a more integrative approach than traditional static stretching which often targets one section of muscles such as the hamstrings; calves, quadriceps.

Active Breathing drills

The bodies physiological response to exercise depends at least in part on one emotional state and perceived ability to cope with the challenge. With so much focus on our physical recover, the psychological aspects for a long time, have been neglected. As far as the body is concerned, stress is stress. Be it physical or psychological the impact is the same.

The aim of breathing in this context is to get the heart, brain and body back into a parasympathetic state. This in a nutshell is reducing the stress hormone cortisol and increasing the relaxation hormone serotonin.

In effect, breath work allows us to self-regulate our states of stress. Like anything it is a skill and with good consistent practice will become an effortless and life changing habit.

Watch the following video for a brilliant drill to incorporate after your sessions

Venous return and the wall drill

This great and simple technique is designed to redirect blood flow from the lower limbs to the bodies centre of mass. By placing the legs up a wall the body is able to create equilibrium and shunt blood back towards the heart. It requires the person to completely rest and use of slow and deliberate breathing helps to focus the mind. Here is a sample you may try

Passive Neural recovery:

These techniques are designed to enhance physical recovery via the passive means of another thing or person. For example a massage therapist is employed to focus on the myofascial realignment to restore muscular symmetry.

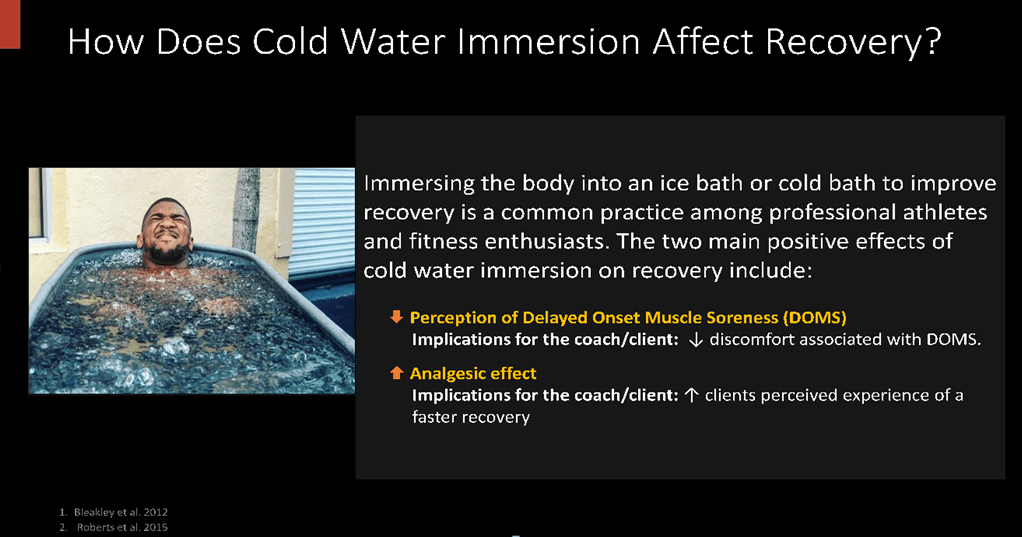

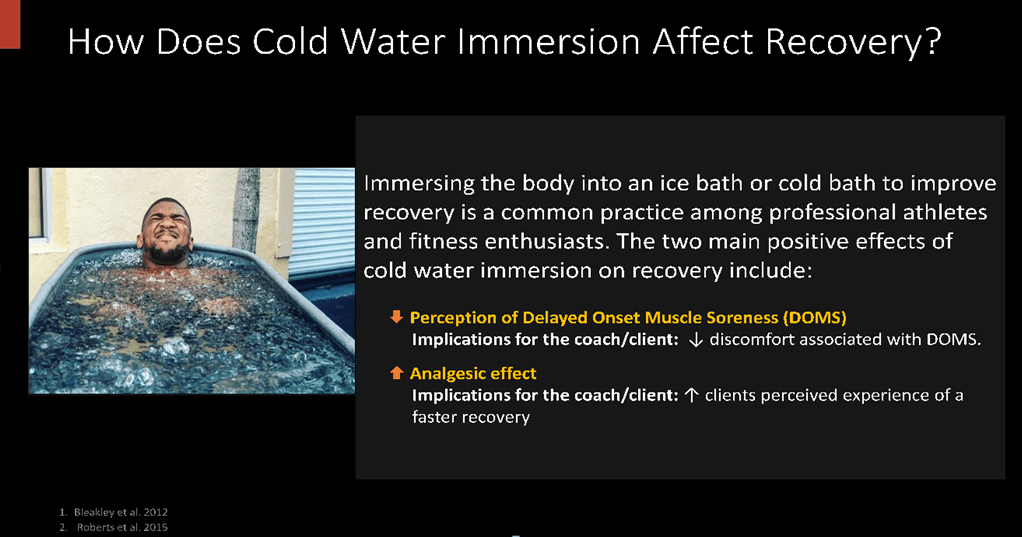

An ice bath is designed to eliminate the build-up of toxins and lactate acid within the body. The thing i.e. the ice bath is designed to allow you to passively recover with next to no effort (even if your freezing your “you know what” off initially)

Massage

Psychological recovery

Whilst the Bio (physical) factors directly affects the psycho (psychological) elements of recovery for the sake of segmenting the following techniques are what one would describe as psychologically enhancing in nature. They include but are not limited to the following:

Flotation therapy

- Floating was original known as “sensory deprivation” but this quickly changed when sales companies realised how damaging this could be to their brands of float tanks

- Neuroscientist John C. Lilly use float tanks to treat behavioural disorders & in 1977 he published the book “The Deep Self” which explored how float tanks could expand a person’s awareness of their internal state.

- In a 2018 study, researchers from the Swedish Défense University reported immersion in a float tank may be useful for reducing negative symptoms related to stress and anxiety among a group of competitive golf players.

- Sleep: As everyone requires different amounts of sleep depending on biology and environment i.e. epigenetic factors like amount of exercise, stress levels and most importantly quality of sleep, typically a good range to aim for is between 7-8 hours of uninterrupted sleep.

Watch this great educational video on the science of sleep by Matt Walker ‘sleep is your superpower’

- Sleep augmentation

One way we can influence our ‘pre-sleep’ is to downregulate cortisol and upregulate melatonin, the hormone that regulates the ‘sleep-wake’ cycle. We can do this by influencing our environment and employing inexpensive strategies such as:

- Wearing night shades/dimming lights/axing tech screens 2-3 hours before sleep

The goal here is to reduce the negative effects of Blu-ray lights which upregulates cortisol and disturb our circadian rhythm and is found when watching TV or playing with our phone or laptops.

https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/blue-light-has-a-dark-side

- Mindfulness/meditation/breath work

All of the above when practiced consistently over a period of a relatively short span of time (4-6 weeks) will induce a plethora of positive effects such as can be found in this article:

https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/12-benefits-of-meditation

The goal of meditation and mindfulness is to de-stress the bio-psycho components and centre the individual to be more present and calm in mind. For a great breakdown on the what and how of mindfulness check out this article which provides insights into how the brain chemistry shifts when mindfulness and meditation techniques are implemented consistently.

Try this simple and easy method after your next training session

Progressive relaxation method

Substrate/nutritional recovery

Eating for recovery whilst important, has been overstated in recent times. For example, consuming protein & carbohydrates to promote repair and growth; does not need to occur strictly within a 60-90-minute window. Sports nutrition authorities such as the Sports Dieticians Australian recommend consuming protein and carbohydrate within a 12-24 hours period following exercise, unless you plan to exercise again a short time later. This notion has also been supported by renown body building and nutrition research Brad Schoenfeld who states ““there is nothing magic about the 20, 30 or 60 minute window following a workout”. “The benefit comes from comes the protein itself, not the exact timing of its consumption”.

Asides from the question on timing, some general nutritional guidelines to promote recovery include:

- Eat foods rich in carbohydrate to promote the replenishment of muscle glycogen (fuel stores). Choices can include: grains, cereals and legumes

- Include lean sources of protein for muscle repair. Choices can include lean meats, low-fat dairy and nuts

- Drink to thirst; unnecessarily drinking large amounts of fluids can promote hyperhydration which can be equally if not more damaging to recovery than dehydration. Therefore, it is recommended you drink fluids to satisfy your thirst.

Nutritional Supplementation

Several studies have shown that taking high doses of antioxidants might blunt the training adaptation to exercise. Other research suggests avoiding the consumption of recovery supplements such as sports drinks and bars might also be advantageous for recovery; the reason being is that leaving the body under a bit of stress for a little while longer, following training might actually ENHANCE the adaptations you get from that exercise session. The What is important to note, is the guidelines above are consistent with the Australian Healthy eating guidelines and by following a simple, but healthy diet all of your nutritional, recovery needs are likely to be achieved.

How tech is augmenting the process of recovery

Helping the body relax after exercise is an important pillar of recovery. With the increasing recognition of the importance of psychological recovery, many fitness enthusiasts are turning to meditation and relaxation apps. Whilst convenient and often helpful, the use of an App particularly for relaxation and stress reduction should never replace the advice from a trained mental health practitioner such as a registered psychologist.

Furthermore, the use of an app for recovery or health, does not come without risk. To assess the quality and robustness of a health-based App; it is recommended you follow the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners advice for health-based apps:

- Review the App’s description, user rating and reviews

- Identify if the app is intended for its use

- Check that the app uses simple and clear language

- Check that the information within the app; comes from reliable and respected sources (i.e. is evidenced based)

- Check that the app is registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) if it claims to be a medical device

- Ensure the app is secure and will not breach your privacy. There should be terms and conditions section that lists its privacy measures and also informs you how any data you enter will be used and collected.

Recommended Apps for Recovery

- Psychological recovery and reducing stress → Muse, Happify, Brain.fm, headspace, pacifica, worry watch, MindSPort, Sanvello

- Breathing app → breath 2 relax

Reference List

- Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136.

- Paolini, J. (2009). Review of myofascial release as an effective massage therapy technique. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training, 14(5), 30-34.

- Schroeder, A. N., & Best, T. M. (2015). Is self myofascial release an effective preexercise and recovery strategy? A literature review. Current sports medicine reports, 14(3), 200-208.

- Nuzzo, J. L. (2020). The case for retiring flexibility as a major component of physical fitness. Sports Medicine, 50(5), 853-870.

- Weerapong, P., Hume, P. A., &Kolt, G. S. (2004). Stretching: mechanisms and benefits for sport performance and injury prevention. Physical Therapy Reviews, 9(4), 189-206.

- Guissard, N., &Duchateau, J. (2006). Neural aspects of muscle stretching. Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 34(4), 154-158.

- Hashim, H. A., Hanafi, H., & Yusof, A. (2011). The effects of progressive muscle relaxation and autogenic relaxation on young soccer players’ mood states. Asian journal of sports medicine, 2(2), 99.

- Solberg, E. E., Ingjer, F., Holen, A., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Nilsson, S., &Holme, I. (2000). Stress reactivity to and recovery from a standardised exercise bout: a study of 31 runners practising relaxation techniques. British journal of sports medicine, 34(4), 268-272.

- Furrer, P., Moen, F., & Firing, K. (2015). How Mindfulness Training may mediate Stress, Performance and Burnout. Sport Journal.

- Vempati, R. P., &Telles, S. (2002). Yoga-based guided relaxation reduces sympathetic activity judged from baseline levels. Psychological reports, 90(2), 487-494.

- Lilly, J. C. (2007). The deep self: Consciousness exploration in the isolation tank. Gateways Books and Tapes.

- Broderick, V., Uiga, L., & Driller, M. (2019). Flotation-restricted environmental stimulation therapy improves sleep and performance recovery in athletes. Performance Enhancement & Health, 7(1-2), 100149.

- Bonnar, D., Bartel, K., Kakoschke, N., & Lang, C. (2018). Sleep interventions designed to improve athletic performance and recovery: a systematic review of current approaches. Sports medicine, 48(3), 683-703.

- Sports Dietitians Australia (SDA). 2020. Recovery Nutrition – Sports Dietitians Australia (SDA). [online] Available at: https://www.sportsdietitians.com.au/factsheets/fuelling-recovery/recovery-nutrition/ [Accessed 9 July 2020].

- Merry, T. L., &Ristow, M. (2016). Do antioxidant supplements interfere with skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise training? The Journal of physiology, 594(18), 5135-5147.

- Paulsen, G., Hamarsland, H., Cumming, K. T., Johansen, R. E., Hulmi, J. J., Børsheim, E., &Raastad, T. (2014). Vitamin C and E supplementation alters protein signalling after a strength training session, but not muscle growth during 10 weeks of training. The Journal of physiology, 592(24), 5391-5408.

- Paulsen, G., Cumming, K. T., Holden, G., Hallén, J., Rønnestad, B. R., Sveen, O., &Buer, C. (2014). Vitamin C and E supplementation hampers cellular adaptation to endurance training in humans: a double‐blind, randomised, controlled trial. The Journal of physiology, 592(8), 1887-1901.

- Bjørnsen, T., Salvesen, S., Berntsen, S., Hetlelid, K. J.,Stea, T. H., Lohne‐Seiler, H., &Haugeberg, G. (2016). Vitamin C and E supplementation blunts increases in total lean body mass in elderly men after strength training. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 26(7), 755-763.

- Rist, B., & Pearce, A. J. (2017). Improving athlete mental training engagement using smartphone phone technology. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 7(3), 138.

- org.au. 2020. RACGP – Recommending Health Apps. [online] Available at: https://www.racgp.org.au/running-a-practice/technology/mobile-devices-to-support-care/recommending-health-apps [Accessed 9 July 2020].

For for Newsletter