Movement screening has become an integral part of the fitness industry with the hopes that fitness coaches can prescribe fitting movements for their clients and reduce the likelihood of them becoming injured during training.

This article is to dissect the real-world application of screening, and if identifying high risk factors with a screening intervention prior to training is better than training without a scored risk factor.

I want to offer an alternative perspective, where the assessment of movement quality plays an important role in an exercise setting, although with a primary focus of guiding safe and effective exercise prescription, rather than highlighting injury risk.

What are we really screening?

Screening describes a strategy used to identify pathological conditions prior to an individual showing the specific symptoms of that condition.

But for that to work, there has to be an early detectable stage with a clear relationship between the dysfunction observed and the injury associated. You also have to show that training to correct the dysfunction will reduce the likelihood of the injury occurring, as well as show if the dysfunction needs early intervention, or can be done later in the training cycle, none of which is strongly supported by evidence from multiple systematic literature reviews.

Although it seems logical that the way someone moves will affect their risk of injury, mechanisms for injury are extremely complex and multifactoral.

An injury occurs when the physical load placed upon tissues of the body outweighs the capacity of the tissues to tolerate that load. In the case of an acute injury, this capacity is the point where intrinsic and extrinsic factors meet, and they overcome the tissues load management capabilities during a specific action or task and at a singular moment in time.

An example of that using a runners hamstring injury would be the likelihood of a runner obtaining a hamstring tear comes down to the cross-over of the extrinsic factors including strength, range of motion, endurance, current action (e.g high-speed running or any changes of direction), their level of acute or chronic fatigue, as well as neuromuscular coordination, balance, movement quality, and asymmetries. And, the intrinsic factors including age, sex, previous injuries; things about the athlete that cannot be changed through training influence.

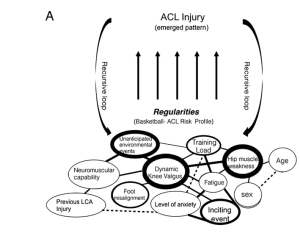

The above table is a hypothetical pyramid of injury risk using the factors mentioned above. Although in isolation, these factors won’t contribute much to an injury, it is only in combination that the risk of injury becomes more probable. The more of these factors you stack onto your athlete, the higher the risk of injury.

Moving from “Screening for risk of injury” to “movement quality assessment to inform exercise prescription”

The majority of human health conditions are complex. The multifactorial complex nature of sports injuries arises not from the linear interaction between isolated and predictive factors, but from the complex interaction among a web of determinants.

The majority of human health conditions are complex. The multifactorial complex nature of sports injuries arises not from the linear interaction between isolated and predictive factors, but from the complex interaction among a web of determinants.

So intercepting an injury risk through screening isolated factors to the risk may send you in a reoccurring loop without solving the dysfunction. (see table below)

As you can see at the top is the injury occurring, the bottom is all the different varying influences that impact the injury arising. As you can see, if you screen and train for single factors (E.g hip muscle weakness and dynamic knee valgus) then throw them back to the web of factors (determinants) it will be inevitable that the injury will arise again once regular training or sport resumes.

The importance of Movement Quality

Good movement quality is defined by the execution of fundamental movements in a balanced and well-coordinated manner. Conversely, poor movement quality presents in the inability to complete these same movement tasks in accordance with accepted theoretical norms (e.g excessive knee valgus during a lunge).

Prioritizing optimal technique is an important consideration among coaches when prescribing and delivering an exercise program. The continual practice of exercise with poor technique can lead to the development of undesirable motor patterns, muscular imbalances, and postural deviations, which are all increasing and contributing risk factors.

How does screening movement quality guide exercise prescription?

All movement assessment tools share a key similarity: they assess fundamental movements to provide a measure of movement quality. This, at a minimum, can provide a level of competency to enter or start a workout routine. Then the coach can qualify that person to perform certain exercises, variations of other exercises, and accessory work needed to later be able to perform other, more complex exercises.

So at the start, it is a matter of identifying what can the athlete perform well and not so well.

But movement quality assessments offer further value in exercise settings.

Assessing movement quality during a workout can provide you with information unobtainable through individual joint, muscle, and movement assessments. You will see how the movement quality is sustained during fatigue, heavier load, neuromuscular control, different levels of attention etc. From this assessment data, the coach now has a deeper view of the dysfunction and can intercept accordingly and confidently.

E.g A client who has a knee valgus during squats presents only very mildly during the initial assessment but in training, you notice the knee valgus increases to a high risk dysfunction once the athlete is at a certain fatigue level. From here, we now know that the dysfunction can be narrowed down to a fitness issue, or a muscular endurance issue which can be intercepted by adding additional HIIT on the rower for low impact VO2max improvements, and wall sits for muscular endurance. Otherwise, if we just use the initial assessment the athlete would be forever programmed ‘medial knee’ corrective exercises to improve strength and neuromuscular control, when the issue may lay within a lack of fitness.

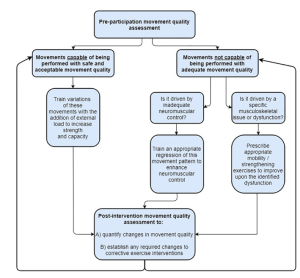

The table below shows assessing movement quality to inform exercise prescription.

The table below shows assessing movement quality to inform exercise prescription.

List the movements the athlete is currently capable of performing with good movement quality and train these movements with progressive overload.

List the movements the athlete is not currently capable of performing with good movement quality and set out interventions progressing them towards the functional movement goal.

Once quality movement is achieved across the fundamental human movements, training can then be pushed to see where and what the breaking point is before the dysfunction arises again, which will be noted and intercepted.

How to apply this to FTI’s movement assessment in the adaptive training system.

FTI’s adaptive functional training system allows coaches to easily periodize and navigate their clients through safe and effective workout programs.

It works through a 5 pillar progressive system, starting with the initial movement quality assessment, from which the coach can highlight the movements to program for performance and movements to regress and work towards improving the quality. The first is the ‘restore function & movement mobility’ pillar. This is programming all the accessory work needed to get a client to a base competency of movement quality. From there, the second pillar is ‘bodyweight application’, teaching the athlete how to perform fundamental movements with no external load. Pillar number 3 is ‘loaded movement’, where you would already be training your athlete in the movements in which they are already competent, but are also working towards the movements in which they are less competent, and not yet ready to load. Pillar number 4 is ‘developing strength and power.’ Once good movement quality is achieved, that movement pattern can be progressed with progressive overload. In pillar 4 your movement quality assessments will highlight a further issue that the initial assessment might not have picked up, like a weakness within a joint, how they handle maintaining good technique with increased volume and fatigue etc. Pillar number 5 takes the athlete to ‘motor control & complexity,’ wherein the athlete, once unconsciously competent in the fundamentals, complex variations can now be implemented. This can highlight neuromuscular control issues that can be noted to improve on later.

This adaptive training model allows you to progress through different aspects of training where you are competent and where you need to improve all while constantly assessing what the athlete performs well and is to be progressed, and where the athlete needs extra work to steer away from potential injury.

Conclusion

The multifactorial and complex nature of sports injuries arises not from the linear combination of isolated and predictive factors, but from the interaction among several factors combined. So movement assessments may not provide the best platform to simply score a risk of injury to then try to improve the score through training.

Instead, a movement assessment in an exercise setting provides data for programming which exercises an athlete can work towards performance, exercises the athlete needs corrective attention, and identifying the nature of the appropriate corrective attention. This information can be used to guide exercise prescription, enhance training safety, and improve long-term functional and performance outcomes.

For for Newsletter